|

The ACO is a huge symphony orchestra. No doubt it is one of the best in the world, especially among organizations focusing on contemporary music. The group, now lead by Steven Sloane, is very refined and plays with incredible precision. They masterfully handle the demanding rhythmic complexities of today's symphonic music. The irony that the large symphonic orchestra is an anachronism, a medium considered irrelevant by many contemporary composers, makes the ACO all the more fascinating.

|

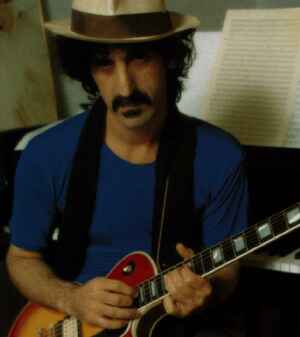

This concert, as the title implies, consisted of two parts. The first half featured the works of three emerging American composers; Brian Robinson (b. 1964), Hsueh-Yung Shen (b. 1952) and Dan Coleman (b. 1972). All three were world premieres, commissioned by the ACO. After an intermission, there was the music of Frank Zappa (1940-1993), arranged for orchestra by Ali N. Askin.

In Search of the Miraculous by Brian Robinson consists of nine mutually contrasting sections of music, arranged so that the end of one overlaps another. The structure is based on a geometric figure called the enneagram, consisting of various lines connecting nine equidistant points along a circle. According to the composer's notes, the process of composing to a precast geometric framework "miraculously" brings forth intuitive, unpredictable, evanescent and magical phenomena in sound. The result is, in my opinion, magnificent.

Robinson's piece starts of sounding like a wonderful jazz band playing at some raucous party off in the distance. This fades as though we are in a dream into silky harmonious washes of beautiful sound that give way to frenetic rising paths of pizzicato lines moving to high harmonics. We are escorted from one mood to another with elegance and grace. Eventually we hear the jazz band playing again - some kind of samba. Then it is over; we wake up - relaxed and refreshed. What a great start for a program.

Hsueh-Yung Shen's Autumn Fall has many abrupt changes of tonality and character, perhaps very much like the Autumn season. The composer is a very skilled orchestrator. There are restless undercurrents fighting with themselves, sometimes ponderous, and sometimes triumphant. We are then offered sonic images of being underwater in some beautiful lagoon full of gorgeous water lilies - then we are startled as if almost eaten by a shark. The piece moves curiously into a single sustained note, reminding me of the orchestra tuning, and then to a long series of descending scales which transision to a solo violin sounding like a cosmic Theremin. Eventually silence. At the end, I had no idea where I had been, but I wanted to go back and do it again.

L'alma respira, by Dan Coleman, speaks directly to the anachronism of the orchestra. Colemen states in the program notes: "My work may be heard as a song of unrequited love ... a parable for the challenges of composing orchestral music in an age when the medium itself has been frozen in the past. I am distanced from the historical ideals of symphonic music, as [the poet] is distanced from his lover, but in the act of creation I attempt to close the gap." As unrequited love is not a very contemporary theme, neither is this music. Perhaps appropriately, it is dramatic romantic music suitable for a movie based on a mid-nineteenth century novel.

During the intermission, we met some "nice young people". One fellow was twenty-three. He is a devoted Frank Zappa fan. He said he first heard Zappa's music three years ago and was totally won over. He doesn't listen to anything else now. To him, and to the girls accompanying him, attending a performance of Zappa by a classical orchestra was a religious experience. This was their pilgrimage. When I told them I had heard Zappa perform in Atlanta in 1968, I was suddenly a revered disciple who had seen Lord.

These fans were outraged that the ACO was not recording this performance. Apparently there are some union agreements that prevents recording at concerts. This historical performance of Zappa's music was going straight into the ether. Now we know why some Zappa fans are Republicans. That said, I'm sure there were scores of minidisk recorders running in coat pockets throughout the audience. If you are in the the ranks of the Zappa fans, you may have already heard this performance on the internet.

|

The hall was filled with Zappa fans, young and old. They loved the performance; cheering and hooting as though they were at a rock concert. The music was lively, full of energy, happy and fun. Zappa's sarcastic sense of humor pours forth in every measure. At the end, there was a standing ovation with shouts of "Zappa, Zappa, Zappa". I have never heard such a positive response to an orchestral performance. Sure, there are occasional standing ovations at the ACO, and once in a while someone (often my wife Juli) will get carried away and yell out "Bravo", but this was something else entirely. The usual gray haired AC O audience was amazed. I was very glad that they got to see first hand people who are passionate about music, not just intellectually satisfied or musically stimulated.

Most visitors to electro-music.com are probably familiar with Zappa's music to some extent. It moves along at a continually rapid pace with long complex runs, often in difficult meters. There are many sudden tempo changes as well. When I heard Zappa and his musicians play in the 60's, I was amazed at how tight the band was. The precision was virtually perfect. The music often has counter rhythms. Zappa was fond of 3 against 4, 4 against 5, 5 against 8, and, in later works for the Synclavier (a vintage computer controlled synthesizer), 12 against 13. This music is difficult to perform, and if any orchestra can do it, it would have to be the ACO.

While I loved hearing Zappa's music come to life again, and I couldn't help get caught up in the joy for the experience, it was apparent from the first that no symphonic orchestra, not even the ACO, can do it justice. At first things sounded OK, but as the set wore on, the orchestra was obviously getting tired and things got more and more ragged. This music was written for a small number of musicians who sat very close to each other on the stage, and who played very responsive amplified electric instruments. Zappa's band was very loud. The sound hit the audience directly from powerful amplifiers; totally overpowering room reflections. As Robin Miller often points out, you can not possibly play music in precise synchronization when the players are separated by large distances on the stage; the acoustic delays isolate the musicians in time.

The stage set up of the ACO was not well considered for Zappa's music. The percussion section was spread across what looked like forty feet! The basses were on one side, the electric guitars in the middle and the pianos on the other side. Strings, horns, woodwinds were spread out all over the place. It was obvious, one man, not even the talented Steven Sloane, could wave his arms skillfully enough to tie it all together. Add to that the muddying effect of the "warm" acoustics of Carnagie Hall and the sound was like some spongy memory of a distant jazz band that is heard as through a dream - like in Brian Robinson's In Search of the Miraculous.

Maybe if I had never heard Zappa and his band play live, I too, like the cheering throng, would have thought that this was great. When it was over, I was exhausted. While the crowd roared on, I stood there in silence. I realized that even the passage of 35 years hadn't muddied the sound of Zappa's music that plays in my mind as much as even a great symphony orchestra in a great hall had just done. I thought to myself: the orchestra is obsolete; it can not play the music. The whale has died.

Like Ishmael, I floated off on what seemed like Frank Zappa's coffin pondering what I had just heard. When finally I washed ashore at home, I did what Zappa did at the end of his life; I played my synthesizer. I listened to 11 against 12 for a few minutes and felt fine.

I look forward to the next ACO concert. Hey, it takes more than one harpoon to kill Moby Dick.